Review: TR-49

A little while back, I listened to an interview where inkle’s co-founder and narrative director Jon Ingold talks a bit about the origins of today’s game, TR-49. There, he spins a fairly wild tale about an uncle and a box and some mysterious books: I’ll allow you to watch it in your own time and decide exactly how much of it is true – but evidently this is something a little different to your typical inkle game.

For what it’s worth, inkle are a studio that I have an awful lot of time for – I’ve previously called them the ‘masters of interactive fiction’, and last year's offering, Expelled!, was comfortably within my Top 10 – and here they’re stepping into a subgenre that I adore. It’s what game designer Bruno Dias refers to as Database thrillers: games where you’re digging through some sort of archive, and oftentimes matching up two sets of data (such as pairing people’s photos with their names à la the Roottrees are Dead), and uncovering some larger truth in the process. If we’re going to narrow it down even further, what I really like are those that also include deduction mechanics, such as the aforementioned Roottrees, A Case of Fraud, and about half a dozen games from developer Tim Sheinman, including the upcoming Nazi-hunting detective game, The Ratline.

Suffice to say, it should be a match made in heaven…’s vault, but with that comes some lofty expectations – so let’s see if TR-49 can meet them.

-

Developer: inkle

Publisher: inkle

Release: 21 January 2026

Retail Price (Steam): 6,99€/$6.99/£5.89

As you might’ve figured out already, there’s a significant air of mystery surrounding TR-49. In keeping with that sense of intrigue, you know extremely little about the character you’re playing as. Where other games might spend a minute or two establishing some backstory – that you’re a mariticidal maniac (Overboard!), or some sort of space archaeologist (Heaven’s Vault), or literally Jean Passepartout (80 Days), here you’ve got pretty much just a name to go on: Abbi. That, and, if you’ve got an ear for English regional accents, that you’re some vague flavour of Northern.

It becomes apparent relatively quickly that Abbi also has some pretty significant gaps in her memory: effectively she knows as much about herself as you do. She’s not quite sure what the machine she’s messing around with does, has no real idea who this ‘Liam’ guy at the other end of her radio is, and isn’t even sure how she’s found herself down in this dingy basement to begin with.

Yet, there she is. Her, some ratty old electronics and the most curious of machines: TR-49.

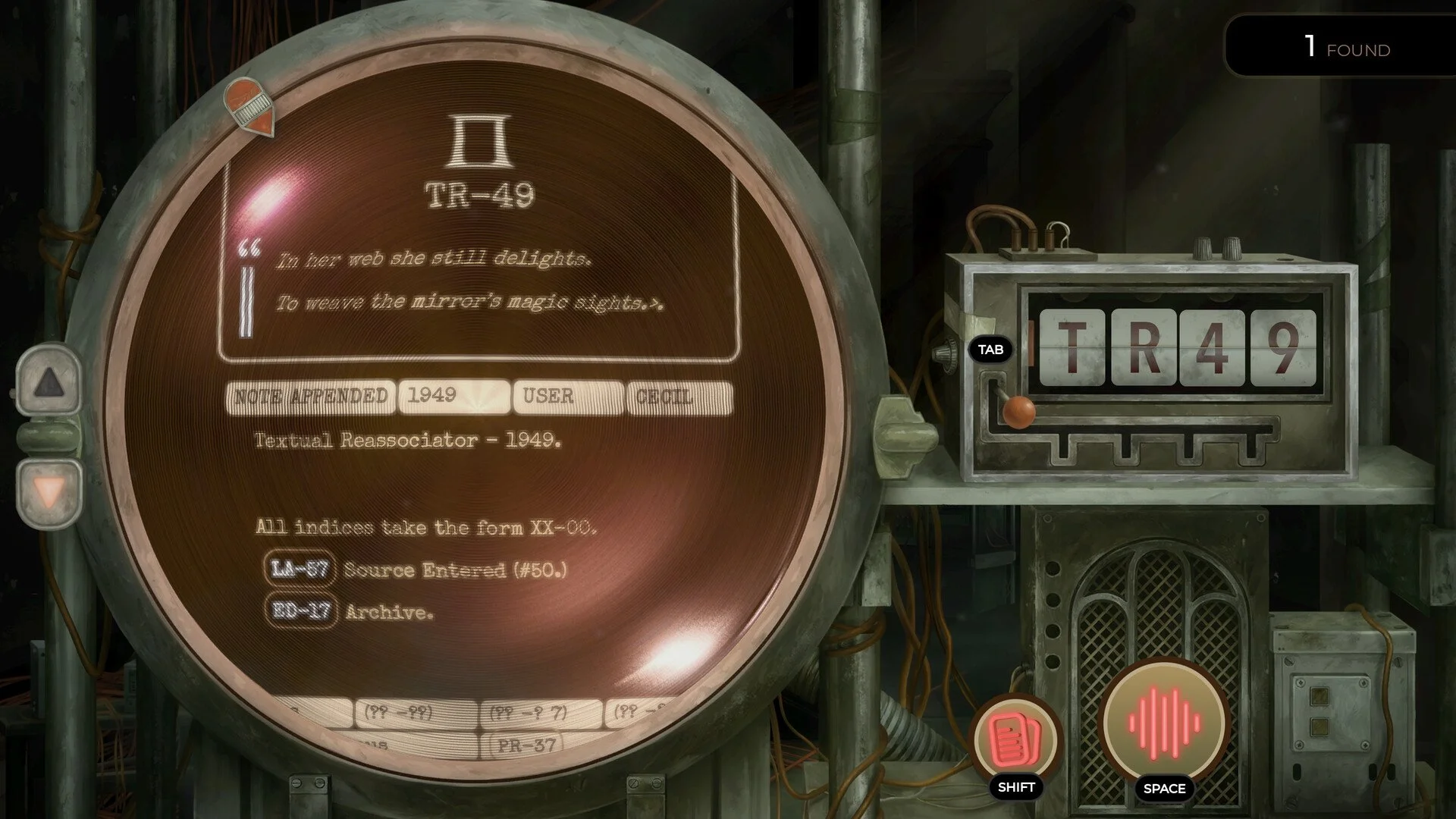

Whatever this thing is, it’s seen better days. She might manage to get it up and running relatively quickly, but from there it’ll be some task to figure out exactly what it’s doing, and that’s before you take into account that an awful lot of its data seems to have been corrupted. However, something that you will establish early on is how the codes have been designated for the vast majority of material within the archive.

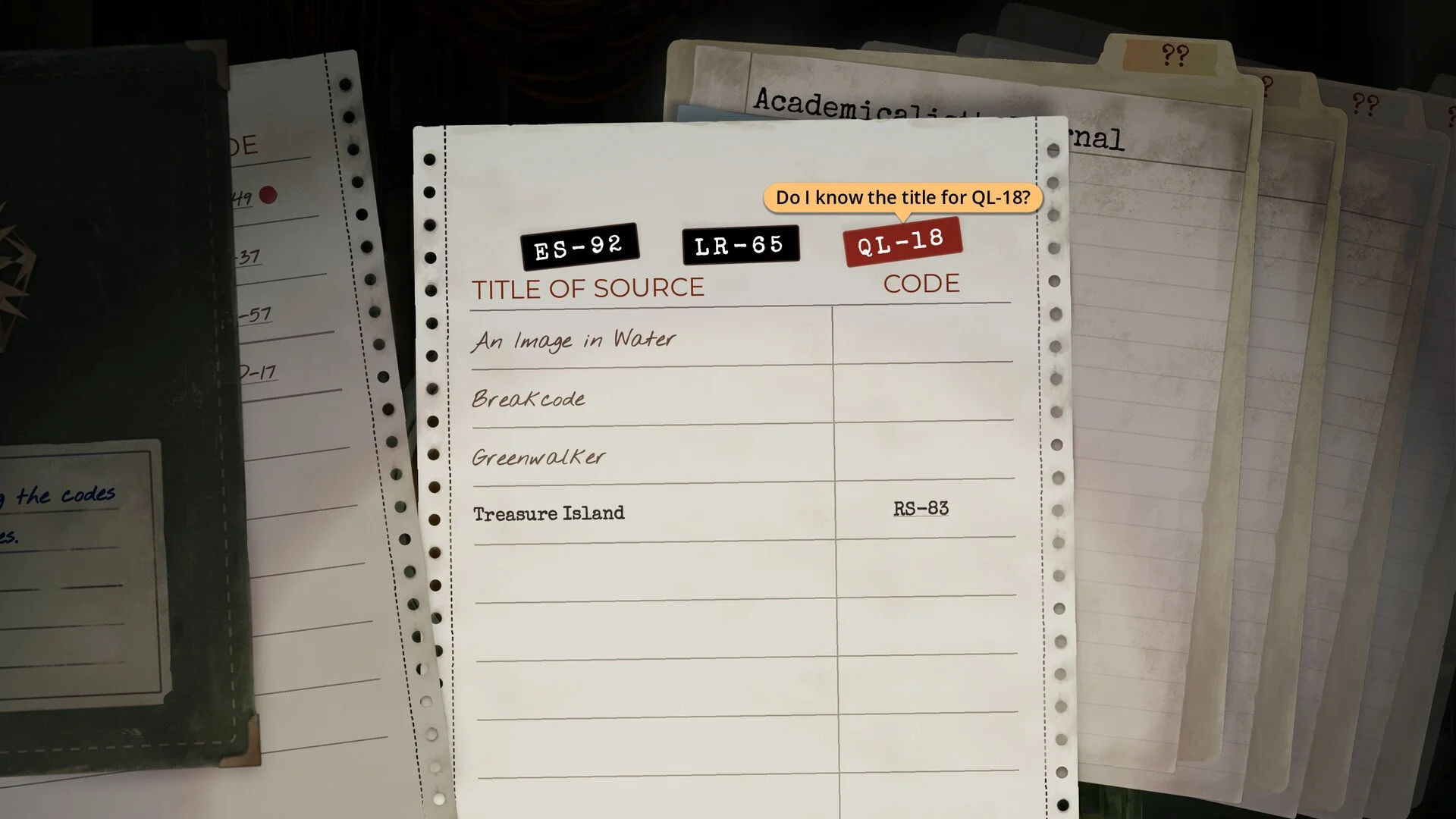

Much like the machine itself, everything archived within it has a four-character code assigned to it: two letters, two numbers, sixty-seven thousand combinations. Not, I hasten to add, combinations which all lead somewhere: you’ll not get anywhere by randomly inputting codes. Instead, you have to deduce those based on TR-49’s filing system. As it’s typically books that have been archived, valid codes usually correspond to an author’s initials and a book’s year of publication – if, for example, you had strong suspicions that Straight Up, the 2011 release from eminent British scholar Danial John Dyer, was in the archive (which would be impressive, as the machine seems to have last been used in the 90s) all you’d need to do is enter DD-11 and the machine would whirl off to that entry.

While I’m not going to confirm or deny Dyer’s presence in the game (okay fine, I’ll deny it), there are a few dozen other classic books buried within TR-49 alongside its original materials. I played the game in two sessions, and between those I jotted down about twenty different titles I wanted to try out, many of which were, pleasingly, there. Often they’re just fun additions, but they occasionally provide players with a small thread to pull on when they’re otherwise stumped – they feel like a little reward for being inquisitive, a bit like inkle patting you on the head and saying ‘well done, here’s a clue to help you out’.

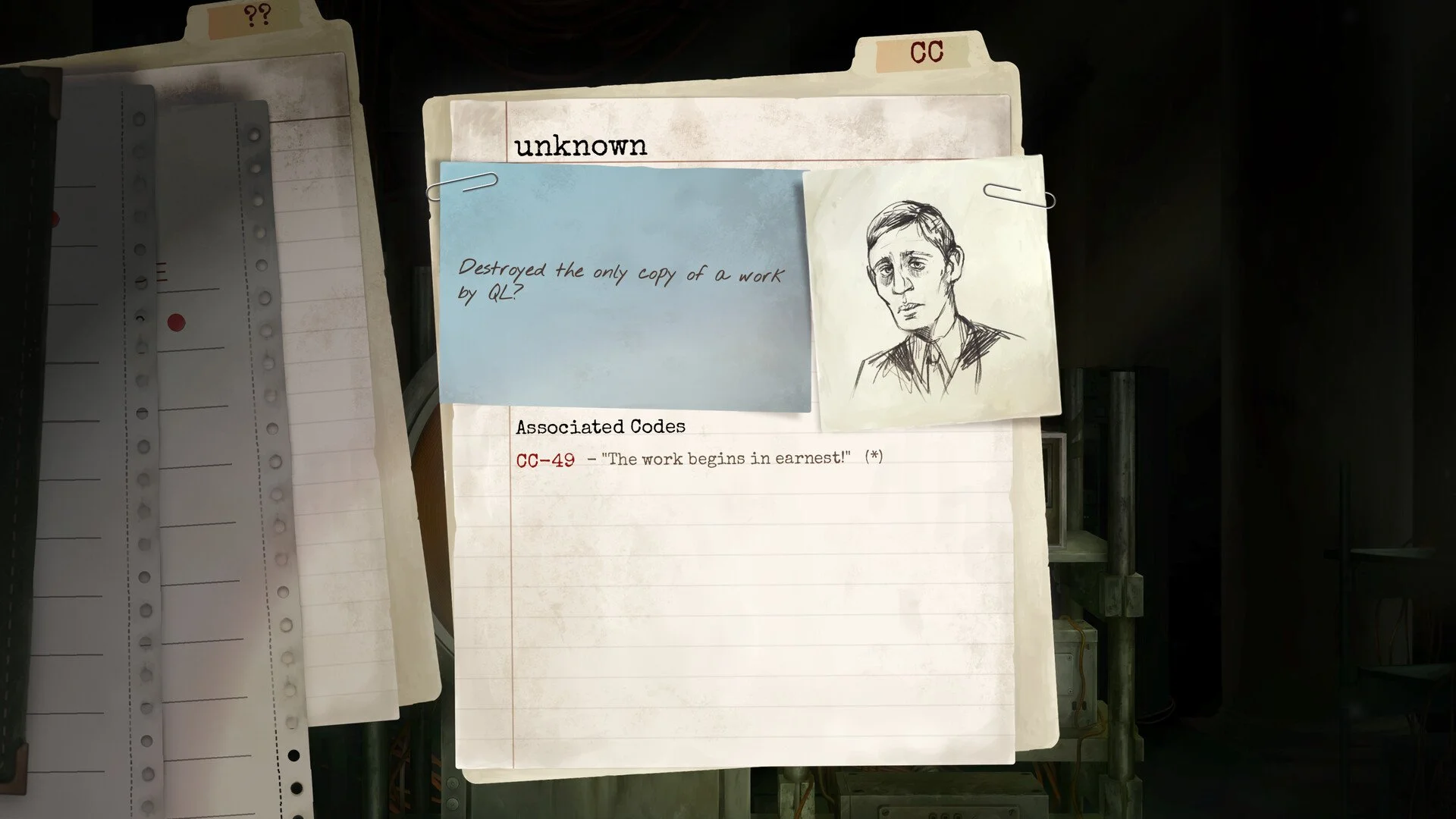

Those clues can guide you towards some useful document within the game’s ‘core archive’: the fifty entries which make up the spine of the machine, and, effectively, the fifty entries that you’re searching for. Those are, of course, all findable without using any external knowledge – you don’t need to use any of those real-world authors or books to navigate the game’s mysteries, and the more sensible way to do it is to follow the paths laid out for you from the start of the game, when you boot up TR-49 for the first time. In addition to those codes you’ll come across a range of titles which you need to assign to each: finding and labelling those fifty items is not the only – or even the main – goal of the game; while there is an incentive to do so, you’re presented with a far more specific task to carry out.

And, though, it does make TR-49 more difficult to talk about, I’ll remain vague on what exactly that task is, as discovering things for yourself is where the soul of this game lies. As players are given such a small amount of information to kick things off, nearly everything feels like a discovery. There are plenty of those which are intriguing enough, giving you some sort of puzzle to work out or some sort of maze to work through, but there were two from my playthrough that stand out several weeks after playing, as they gave me genuine, physical reactions.

There was a drop in the pit of my stomach as one revelation was slowly unravelled after the first hour or so, and a second sent chills down my spine as soon as I entered a code and saw the machine racing off to some other deep, hidden part of the archive — confirming my most worrying of suspicions.

I know I was talking about ‘database thrillers’ at the top of this article but inkle themselves describe the game as the more broad ‘narrative deduction’ genre, which I like as it has two pretty concrete areas to focus on. As mentioned, I don’t really want to reveal anything about the narrative side of things – other than to say it’s brilliant – but I can dig a bit deeper on that other part: deductions.

I would say it’s rare for a narrative deduction game to not weigh more heavily on one of those two aspects, and for TR-49 it’s the narrative part which is doing more of the work. Arguably that’s the way round you’d want it to be: though I suppose that depends on you as a player. I did feel a significant number of the game’s deductions were fairly straightforward: there were a lot of times where the title of an entry was only one step away, or, on a couple of occasions, somewhere on the exact same page.

And, as is the way in many other deduction games, some of the solutions can be somewhat brute-forced: if you knew a book was published by a particular author in the thirties, there’s not much reason you couldn’t just run through IL-30, IL-31, IL-32, and so on, until you landed on the correct code, instead of taking the time to figure out the exact year. The latter would almost certainly be more fulfilling; ultimately you’re only ruining your own fun, like flicking through a choose your own adventure novel without following its directions, but if you really wanted to, once you’ve established an author published a book in a given year, I don’t think there’s anything to stop you just checking all the years surrounding it. Authors only live for so long.

There was one other little trick that felt so on-the-nose that I didn’t try it until I’d almost found and named all 50 sources: it gave me the final two names that I was missing, for a couple of by-then relatively irrelevant articles. It’s worth mentioning that was the closest thing I encountered to the problem you can sometimes get with entirely non-linear games – often these database games – where you accidentally stumble upon the most important information early on. I don’t think that would be likely, if even possible, in TR-49, but you’ll probably have a loose end or two that feel a little anticlimactic to wrap up.

I can’t leave TR-49 without quickly mentioning its voice cast: I’ve thus far neglected the fact that inkle not only describe it as a narrative deduction game but also an audio drama, and they seem really quite proud of the acting in this game. They have every right to be.

The two leads, Rebekah McLoughlin and Paul Warren do an excellent job which adds a huge amount to the game: it would be great without them, but is significantly elevated by their delivery of Ingold’s dialogue. Additional snippets of voice work provide flavour throughout, but it’s a standout performance from Phillipe Bosher which provided yet another instance of something that stayed with me long after I finished the game.

TR-49 is a strong start to 2026, and yet another excellent narrative game from inkle. I don’t want to have to say this every time they release a new title (as I did with Expelled!) but it might well be their best work to date. TR-49 is awarded an 8.5 out of 10 by IndieLoupe.com, and is out today.

The reviewed product was provided on behalf of the developer.